Mapping the Solar System: What We Know and What Remains a Mystery

Introduction: Humanity’s Quest to Map the Cosmos

For centuries, humanity has looked to the skies with a mix of curiosity and wonder. From ancient astronomers charting wandering stars to modern scientists sending robotic explorers across billions of miles, the goal has remained the same — to map the universe and understand our place within it. The story of “Mapping the Solar System: What We Know and What Remains a Mystery” is one of both triumph and humility. We’ve come a long way from the early days of planetary speculation, but vast regions of our cosmic neighborhood still remain uncharted.

Today, thanks to space missions, powerful telescopes, and sophisticated computer models, we have detailed maps of planets, moons, and asteroids that were once mere points of light in the sky. Yet every new image and discovery reminds us that our knowledge of the solar system is far from complete. For every crater, canyon, and icy mountain we’ve mapped, there are countless secrets waiting in the darkness beyond.

As NASA’s Solar System Exploration program puts it, “Mapping space is not just about geography — it’s about understanding the forces and histories that shape worlds.”

Early Maps of the Solar System

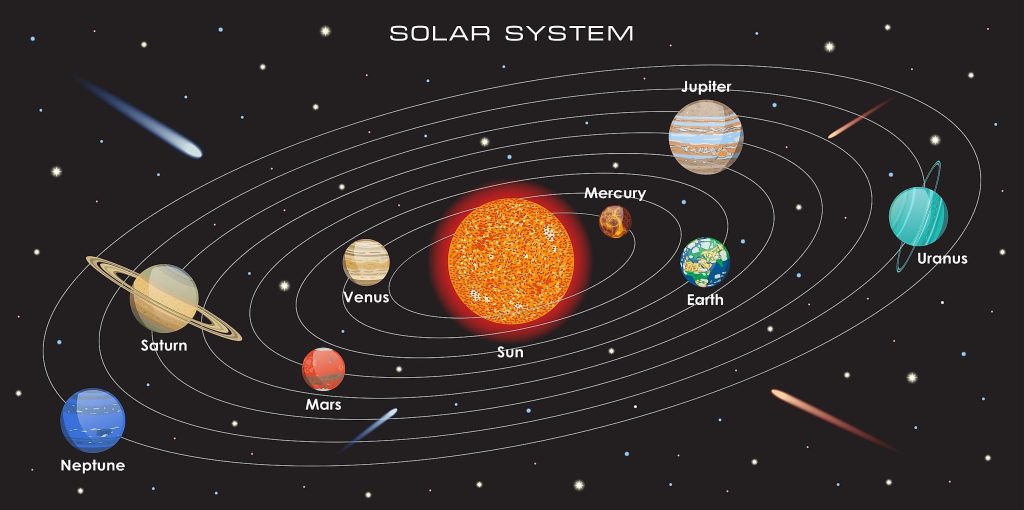

The first attempts to “map” the solar system were not maps in the modern sense but philosophical models of the cosmos. Ancient Greek astronomers like Ptolemy envisioned an Earth-centered universe, while Copernicus later revolutionized that view with his heliocentric model, placing the Sun at the center. These early diagrams, though simple, were groundbreaking steps toward understanding spatial relationships among the planets.

By the 17th century, with the invention of the telescope, astronomers like Galileo and Kepler began to chart the orbits of planets and moons more precisely. Kepler’s laws of planetary motion provided the first mathematical framework for predicting how planets move — effectively giving humanity its first dynamic “map” of the solar system.

In the 19th century, advancements in optics and mathematics allowed astronomers to calculate the positions of previously unseen worlds. This led to the discovery of Neptune in 1846, found not by direct observation but through the careful mapping of Uranus’s irregular orbit — a testament to how maps can reveal the unseen.

Modern Tools for Mapping Planets and Moons

Today’s maps of the solar system are built on data gathered from spacecraft, satellites, and telescopes that span every wavelength of light. High-resolution imagery, radar mapping, and laser altimetry have transformed our understanding of planetary surfaces and compositions.

Among the most important contributors to modern planetary mapping are missions like:

- Voyager 1 and 2 – Pioneers of deep-space exploration, providing the first close-up images of Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune.

- Cassini-Huygens – Mapped Saturn’s rings and moons in unprecedented detail before its dramatic dive into the planet’s atmosphere in 2017.

- Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO) – Used high-resolution cameras and radar to map the Martian surface and detect water ice below ground.

- New Horizons – Revealed the heart-shaped plains and icy mountains of Pluto in 2015, changing our view of the outer solar system forever.

Interactive databases such as USGS Astrogeology Science Center and Planetary Maps of NASA now make it possible for researchers — and the public — to explore the surfaces of other worlds from home.

The Inner Planets: Close Neighbors with Familiar Faces

The inner solar system — Mercury, Venus, Earth, and Mars — is the most thoroughly mapped region of our cosmic neighborhood. Thanks to decades of exploration, we know these worlds in exquisite detail.

Mercury was fully mapped by NASA’s MESSENGER mission, which revealed a world scarred by craters and ancient volcanic plains. Venus, though hidden beneath thick clouds, has been mapped using radar from the Magellan spacecraft, uncovering mountains, volcanoes, and vast lava flows.

Mars remains one of the best-mapped planets beyond Earth, thanks to orbiters and rovers that have charted its canyons, polar caps, and ancient river valleys. These detailed maps have helped identify potential landing sites for future human missions and areas that once may have harbored life.

Our own planet, of course, remains the most familiar — yet even here, mapping continues to uncover surprises. From deep ocean trenches to subglacial lakes in Antarctica, Earth reminds us that exploration begins at home.

The Outer Planets: Giants and Their Moons

Beyond the asteroid belt lie the gas and ice giants — Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune. These massive planets are too large and gaseous to map in the traditional sense, but their cloud structures, magnetic fields, and moons offer a rich landscape for exploration.

Jupiter’s Juno mission has provided remarkable insights into its atmosphere, auroras, and interior structure. The planet’s moon Europa — believed to contain a vast subsurface ocean — has been a focus of mapping efforts as scientists prepare for future missions like Europa Clipper.

Saturn’s system is dominated by its rings and moons, each a world in its own right. Titan, with its methane lakes and dense atmosphere, has been extensively mapped by Cassini’s radar, revealing landscapes eerily similar to Earth’s.

Uranus and Neptune remain largely mysterious, having been visited only once by Voyager 2 in the 1980s. Future missions could finally map their weather systems and icy moons in detail, shedding light on the outermost realms of our solar system.

Asteroids, Comets, and the Kuiper Belt

Between Mars and Jupiter lies the asteroid belt, a region filled with rocky remnants from the solar system’s formation. Missions like Dawn and OSIRIS-REx have mapped and sampled these ancient bodies, providing clues about how planets formed billions of years ago.

Beyond Neptune, the Kuiper Belt extends into deep space — a frozen frontier containing dwarf planets like Pluto, Haumea, and Makemake. New Horizons continues to send back data from this region, revealing a surprisingly diverse collection of icy worlds.

Comets, too, are crucial to mapping the solar system’s evolution. The Rosetta mission to Comet 67P/Churyumov–Gerasimenko gave us the first detailed maps of a comet’s surface, showing cliffs, boulders, and jets of gas erupting into space.

Beyond Pluto: The Search for Planet Nine

One of the greatest mysteries in solar system mapping lies beyond Pluto. Astronomers have noticed strange gravitational effects in the outer solar system — suggesting that a massive, unseen planet might be lurking far from the Sun.

This hypothetical world, dubbed Planet Nine, could be ten times the mass of Earth and orbit hundreds of times farther away. Despite years of searching, it has yet to be found, though surveys with powerful telescopes like ESO’s Very Large Telescope continue to hunt for clues.

If discovered, Planet Nine would not only reshape our maps but also our understanding of how the solar system formed and evolved.

Unanswered Questions and Hidden Frontiers

Even after centuries of observation, many mysteries remain. Why do certain moons — like Enceladus and Europa — show signs of geological activity and potential habitability? What forces shaped the intricate structures of Saturn’s rings? And how much of the solar system’s mass remains hidden in distant, icy debris?

Mapping isn’t just about visual representation; it’s about uncovering stories. Each crater, plume, and shadow tells us something about time, chemistry, and motion. Yet, vast regions — like the dark outer Oort Cloud — remain beyond the reach of current technology.

The next generation of telescopes and probes promises to fill in these blanks, but for now, our map of the solar system is still, in many ways, a work in progress.

The Future of Solar System Mapping

The future of mapping will depend on advances in artificial intelligence, miniaturized sensors, and autonomous spacecraft. Swarms of nanosatellites could one day map multiple planets simultaneously, while drones and landers work in tandem to create real-time 3D reconstructions of alien worlds.

Furthermore, citizen science projects now allow the public to participate. Websites like Zooniverse enable volunteers to analyze planetary images, helping identify craters, dunes, and cloud patterns that might otherwise go unnoticed.

Mapping the solar system isn’t only about collecting data — it’s about building a shared understanding of our cosmic environment. Each new mission extends the borders of human knowledge and prepares the way for future generations of explorers.

A Map Still in the Making

“Mapping the Solar System: What We Know and What Remains a Mystery” is, ultimately, a story about progress and perspective. Our ancestors once saw the planets as divine orbs circling in perfect harmony; today, we see them as dynamic, complex worlds with histories as rich as our own. Yet even now, much remains to be discovered.

As new missions venture deeper into space, the boundaries of our maps will expand, revealing both answers and more questions. The solar system is not static — it’s alive with movement, mystery, and wonder. And as long as humanity continues to look upward, our maps will never be complete.

Si quieres conocer otros artículos parecidos a Mapping the Solar System: What We Know and What Remains a Mystery puedes visitar la categoría Observational Astronomy.